Research

My research focuses on the measurement, prediction, and control of intense beams in high-power hadron accelerators.

Hadron accelerators are essential tools for scientific research. For example, hadron accelerators generate neutrons, neutrinos, and muons for experiments in condensed matter physics, material science, nuclear physics, and particle physics. In the future, hadron accelerators may drive nuclear fission reactors and transmutation of nuclear waste. These and other applications require hadron beams of extreme intensity while satisfying tight constraints on the particle distribution in phase space.

Satisfying these constraints is challenging because of collective effects which drive multiparticle resonances and instabilities in the beam as it evolves. The result is that some fraction of particles do not make it through the accelerator. The radiation generated by these lost particles places hard limits on the beam power. Today, a small number of facilities operate at or above 1 megawatt (MW) beam power, requiring fractional beam loss to be near \(10^{-6}\), or one out of every million particles. A future 10 MW accelerator would need to reduce losses below \(10^{-7}\), and so on as the power increases. This is currently impossible—we can measure low-level beam loss, but we cannot predict or control it to the necessary degree.

Phase space painting

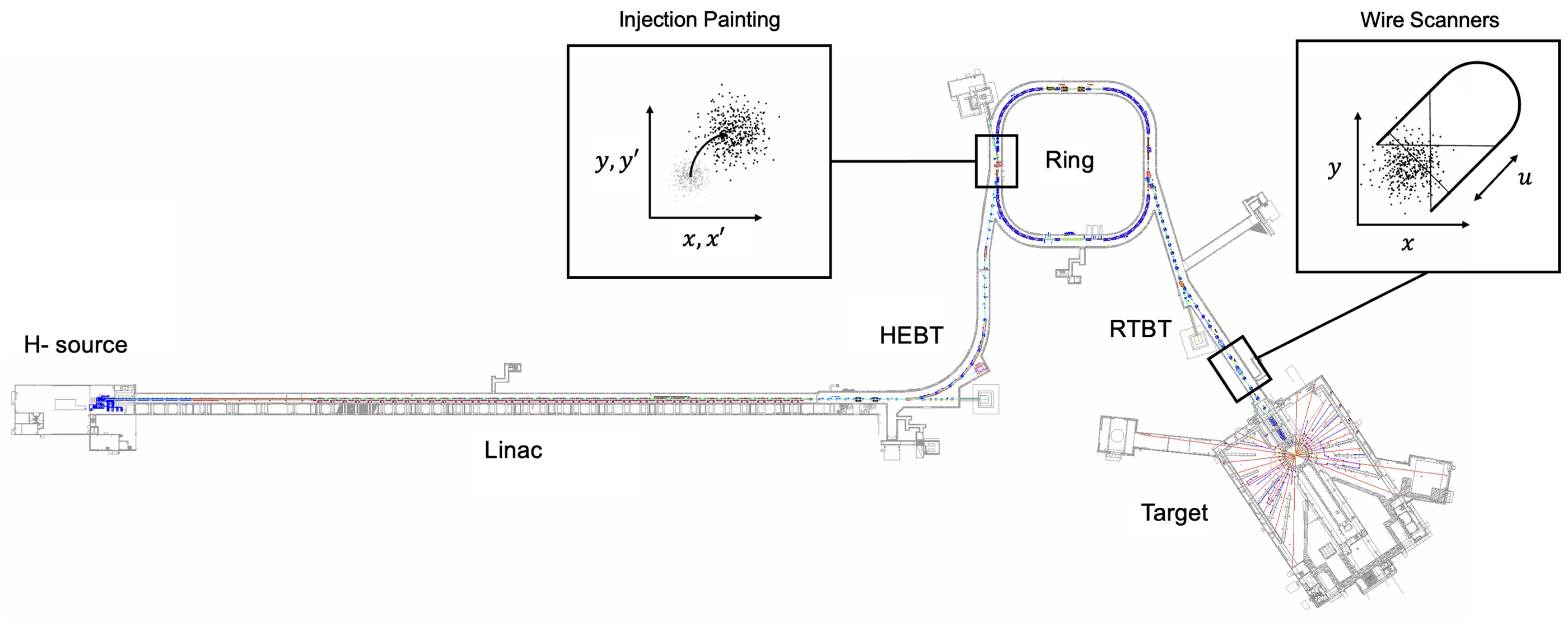

The primary method to generate intense beams is to repeatedly inject small pulses from a linear accelerator (linac) into a circular accelerator (ring). During the beam accumulation, dipole magnets are used to vary the position and momentum of the injected beam relative to the circulating beam. In the frame of the circulating beam, the injection point is moved through the four-dimensional phase space as a function of time. This process is known as phase space painting. Painting is now a vital component of the two operating high-power accumulator rings: SNS and J-PARC.

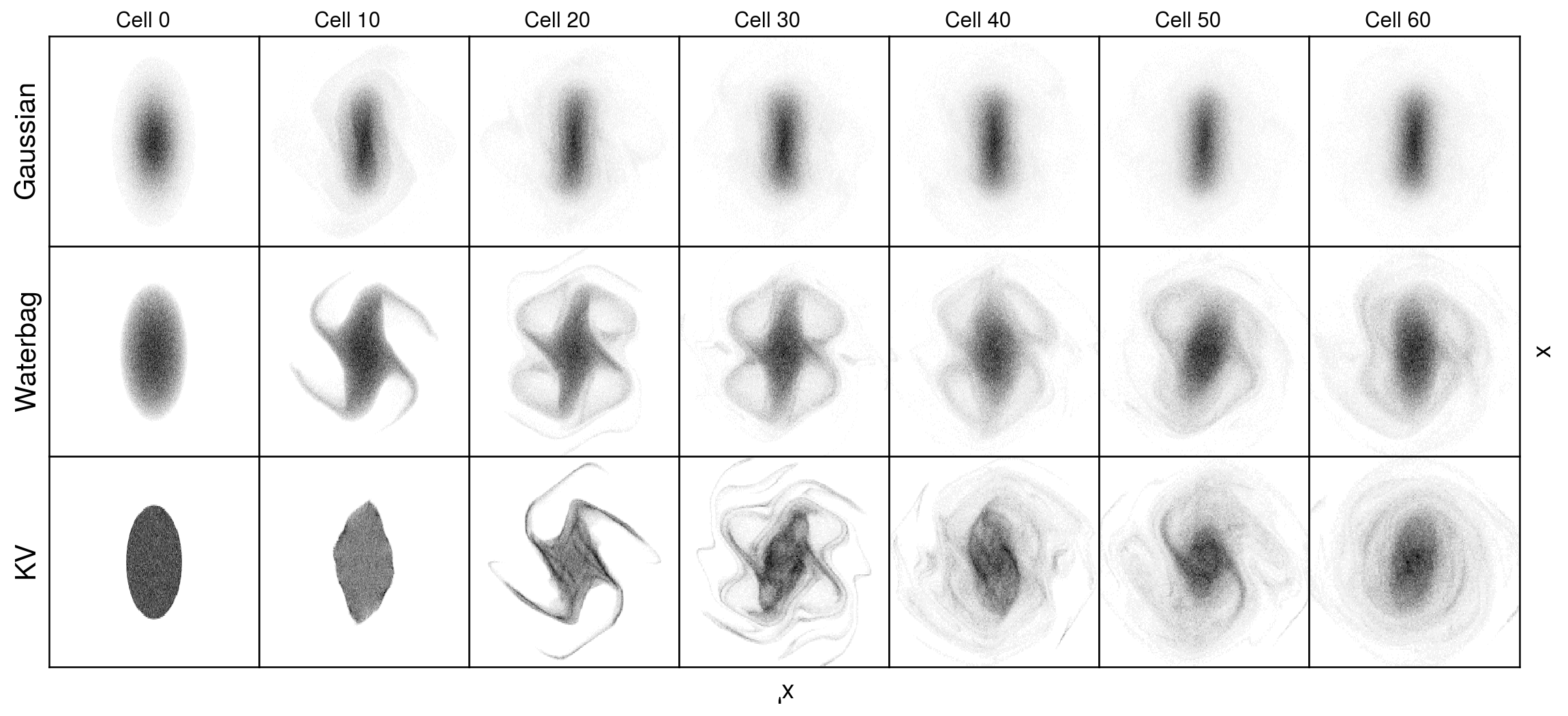

At a basic level, phase space painting is used to avoid high-density regions of charge in the accumulated beam. More detailed control is complicated by self-consistent electrostatic (space charge) forces which act on the beam as it evolves in the ring. The inclusion of space charge means we cannot easily predict what will happen when we propose a new painting scheme—i.e., a path through the four-dimensional phase space—without long simulations.

My current work on this topic focuses on a new painting method that we call eigenpainting, which leverages the theory of coupled linear optics to generate a “vortex” beam in the ring. Other work includes the application of ML methods to develop new 4D or 6D painting schemes in linear or nonlinear lattices.

Beam halo formation and instabilities

Halo-level simulation benchmarking

The combined effects of external and self-generated fields can drive small numbers of particles to very large amplitudes, forming a large, low-density “halo” surrounding a dense core. The fraction of particles in the halo is so small that the halo has almost no effect on the core dynamics and is nearly impossible to measure with conventional diagnostics. However, as described above, it is these particles that ultimately limit the accelerator power.

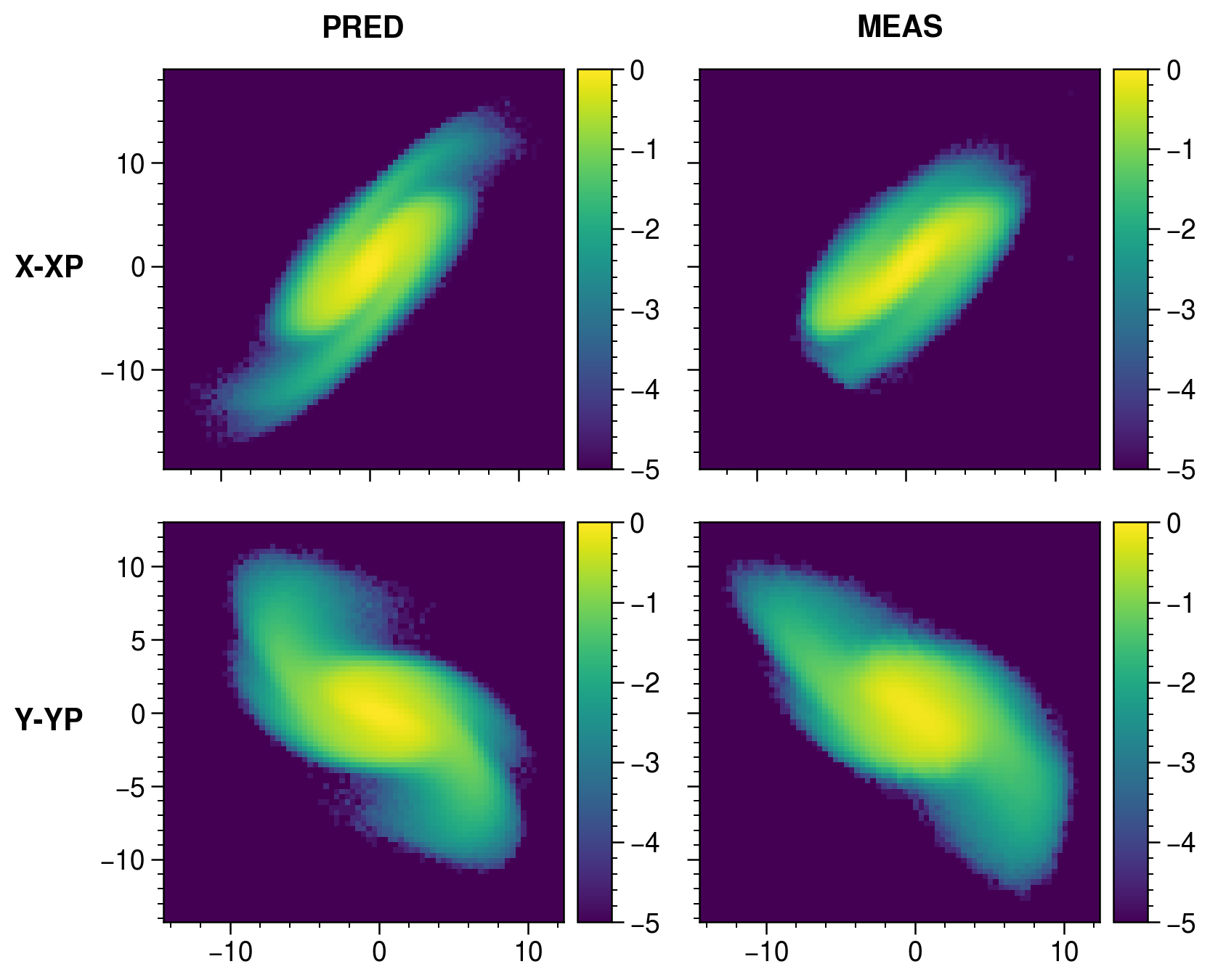

Halo formation is challenging to predict due to its sensitivity to poorly known model parameters; for example, we typically do not know the initial particle distribution in the full six-dimensional phase space. It is also challenging to measure such a faint signal on top of the bright core. We are using the Beam Test Facility (BTF) at the Spallation Neutron Source (SNS) to address these problems. The BTF is a replica of the first few meters of the 400-meter SNS linac. It is equipped to measure the complete initial 6D distribution and the output 2D distributions with six orders of dynamic range—enough to image halo particles. We are leveraging these unique diagnostics to benchmark particle-in-cell (PIC) simulations at a new level of detail and better understand halo formation in linear accelerators.

Hadron bunch compression

A future muon collider (MC) would require extremely short, intense proton pulses to generate the initial muon beam. The proposed scheme uses an SNS-style linac and accumulator ring followed by a separate ring to compress the bunch to a few nanoseconds in length. This extreme bunch compression has not been demonstrated in a hadron accelerator. We’re examining whether a similar bunch compression scheme could be tested at the SNS accumulator ring. In addition to benefiting muon collider designs, bunch compression would provide an opportunity to study the beam dynamics in the SNS at a much higher particle density, which will amplify space charge effects, impedances, and electron cloud instabilities.

Phase space measurement and reconstruction

I have worked on direct high-dimensional phase space measurements as part of the SNS-BTF project described above. In direct measurements, the phase space density is measured using a set of scanning slit apertures. My work focused on developing efficient high-dimensional scan patterns, reducing the scanning time by an order of magnitude. Additionally, I focused on the analysis and visualization of the resulting high-dimensional phase space image.

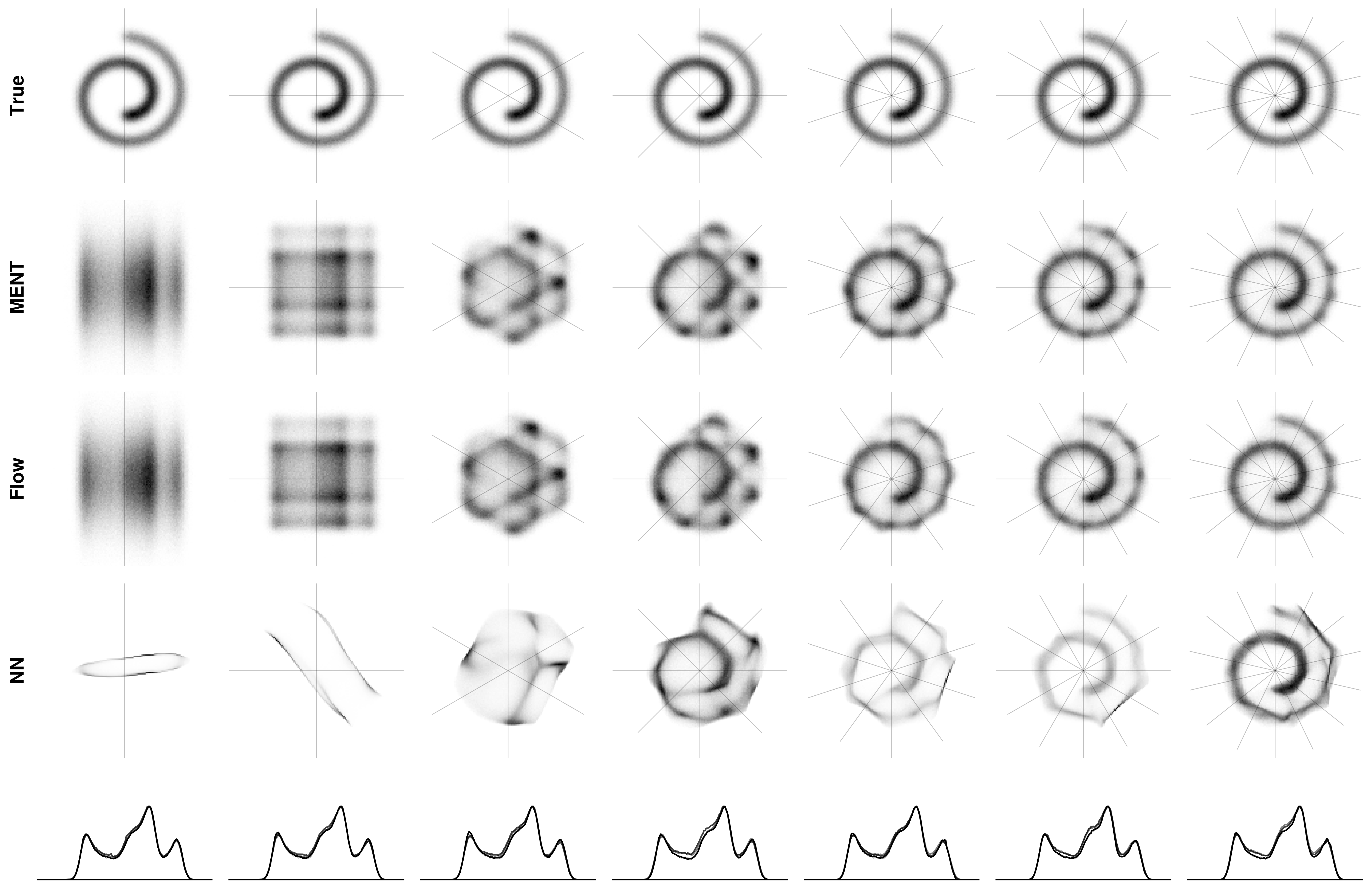

Direct measurements are not always possible; sometimes we have only partial information, such as the projected density along a single dimension. Still, partial information constrains the unknown distribution, and one may attempt to find a distribution consistent with these constraints. I’m in the use of maximum-entropy and Bayesian methods to incorporate prior knowledge and quantify uncertainty in the reconstruction. A particular focus has been the use of generative models and sampling algorithms to extend maximum-entropy techniques to six-dimensional phase space.

Machine learning applications

There are many opportunities to apply ML techniques to optimization and inverse problems arising in accelerator physics. I’m particularly interested in methods that combine ML techniques with physics principles or models. Examples include intra-beam stripping calculations using normalizing flows, differentiable simulations, physics-constrained surrogate models, etc.