N-dimensional MENT via particle sampling

This preprint suggests a new implementation of MENT. MENT is an algorithm to reconstruct a distribution from its projections. It’s a beautiful approach to the reconstruction problem based on the principle of maximum relative entropy (ME) — a very general principle grounded in probability theory. The algorithm turns out to be extremely robust and works for almost all problems I’ve encountered. What’s really nice is that it solves a constrained optimization problem exactly, without any regularization parameter.

MENT was originally developed for 2D reconstructions (i.e. “tomography”), but its author Gerald Minerbo (LANL) was aware that it could work in higher dimensions. In his original paper, Minerbo used MENT to reconstruct a 3D distribution from 2D projections [1]. A few years later, he used MENT to reconstruct a 4D distribution from 1D projections [2]. This was in 1981! It seems like people forgot about this paper. The next paper on 4D tomography wasn’t until the 2000s [3]. Wong [4] recently revived Minerbo’s work and applied 4D MENT to experimental data at the SNS.

It’s not clear if MENT can scale to 6D (or higher). There’s a key step in the algorithm that involves projecting an N-dimensional probability density function (pdf) \(\rho(x)\) onto an M-dimensional plane. For each point on the M-dimensional plane, we have to compute an integral over (N-M)-dimensional space. This can get expensive. My idea is to estimate the projection by sampling particles from \(\rho(x)\) and binning those particles on the projection axis. This is sort of like Monte Carlo integration. The tough part is sampling the particles, which is not necessarily easier than the numerical integration.

I tried two sampling methods. I call the first method grid sampling (GS). When N <= 4, it’s possible to evaluate \(\rho(x)\) on a grid, forming an N-dimensional image or discrete probability distribution. It’s super fast to sample particles from the image using numpy.random.choice. Then, for each bin, we sample a point from a uniform distribution within the bin. Grid sampling isn’t absolutely necessary in 4D problems, but it’s convenient. There are basically two parameters: the grid resolution and a smoothing parameter to hide the checkerboard pattern from the discretized pdf. It’s easy to choose the grid resolution: make it as high as possible. I find \(32^4\) bins are enough for most distributions, but my computer has no problem storing \(50^4\) or more bins.

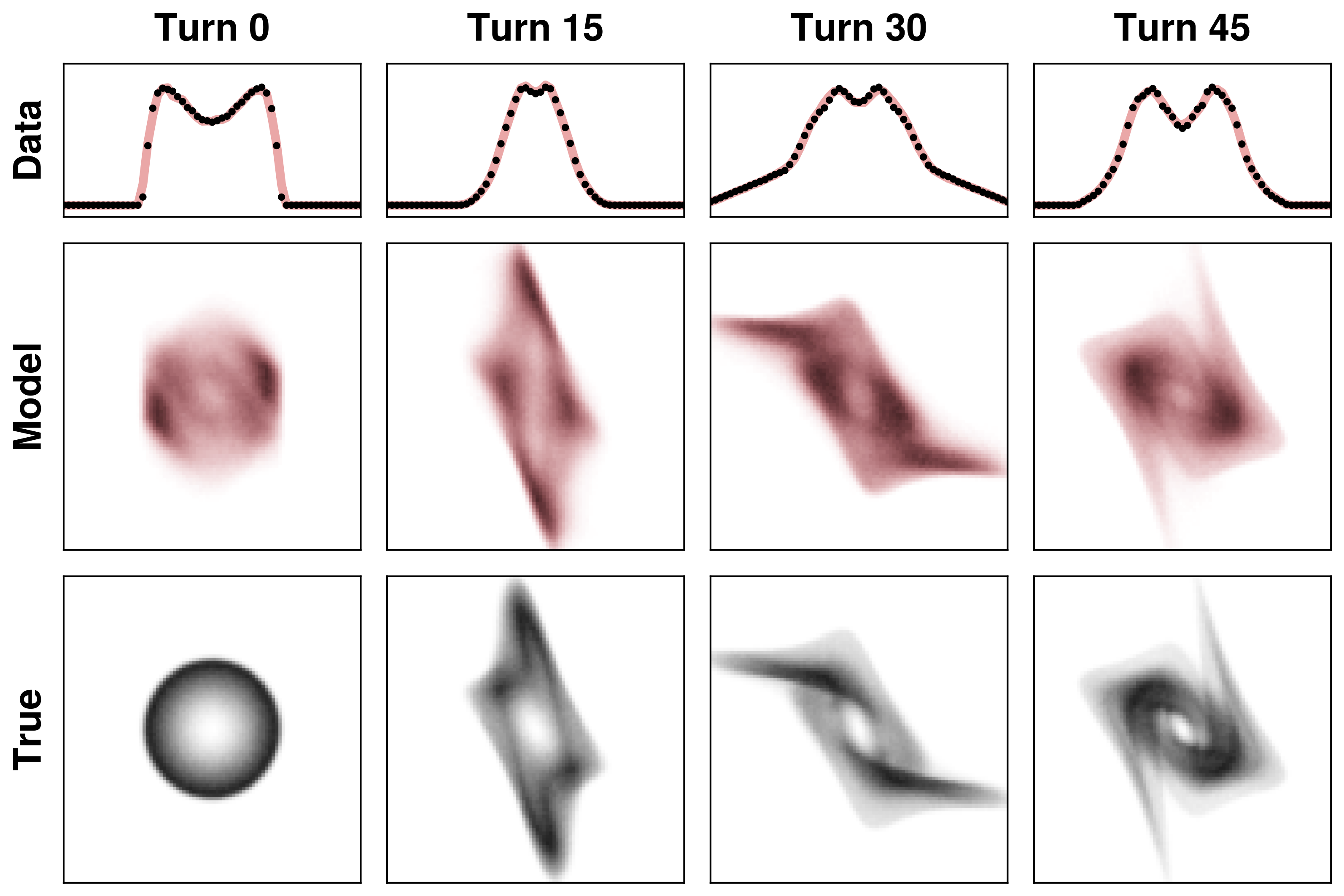

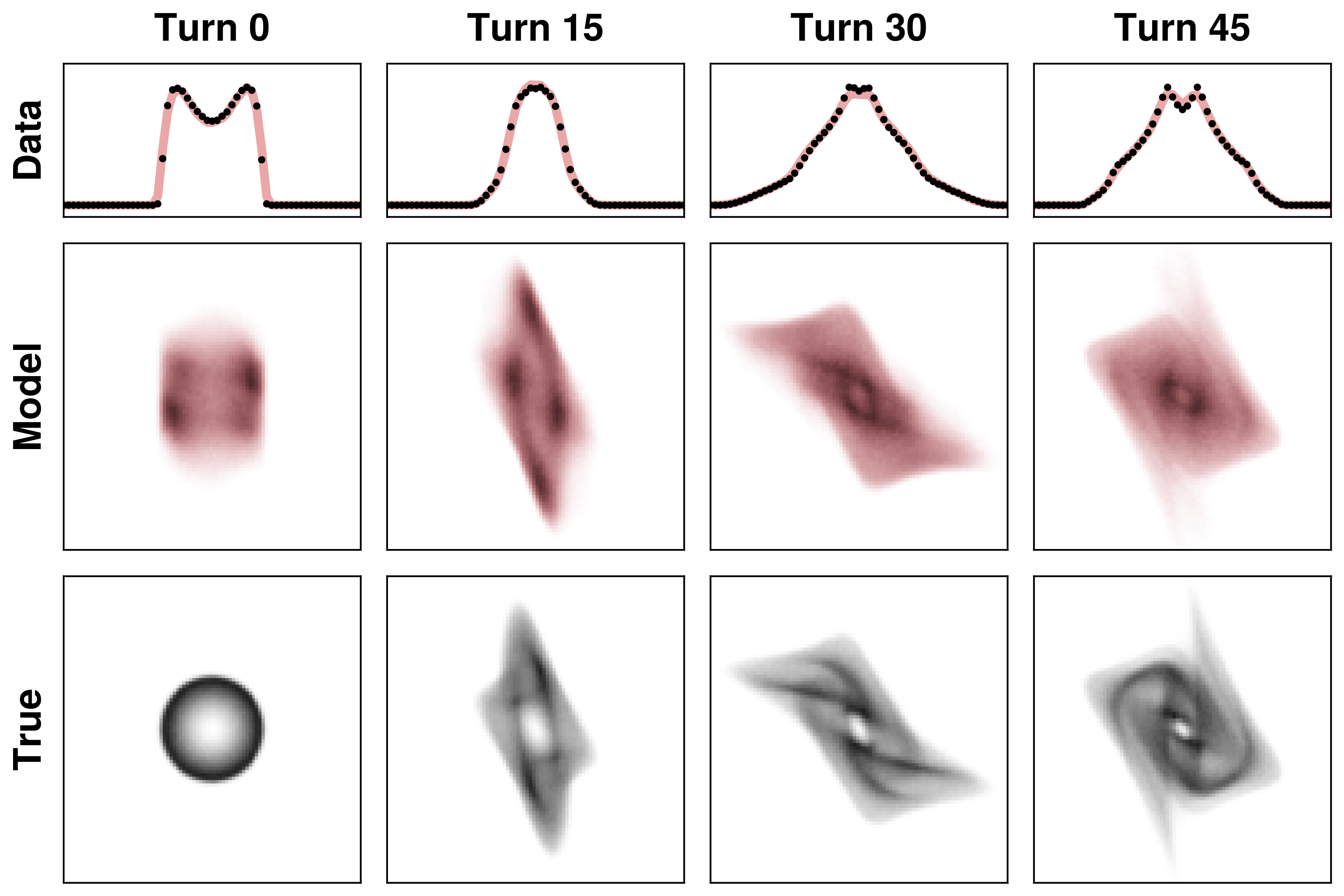

I tested this approach by fitting a 4D distribution to 1D projections in a highly nonlinear system. The system is essentially a 2D harmonic oscillator with a nonlinear force applied after each oscillation period. The following plots show the 1D projections in the top rows. There isn’t enough data here to constrain the 4D density, so the reconstruction is inaccurate. But that’s not the point of this example: the only point was to fit the data.

Grid sampling doesn’t work in higher dimensions because of memory constraints, but there are other algorithms to sample from high-dimensional distributions. One is called the Metropolis-Hastings (MH) algorithm, which is a variant of Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). MH requires access to the unnormalized probability density, but nothing else. It’s surprisingly simple.

The only problem with MCMC is that it’s slow. MCMC is often used for Bayesian inference, where the goal is to compute an expectation value under the distribution. Expectation values can usually be estimated from a few hundred or a few thousand samples, but computing projections requires many more samples—possibly millions if we want to capture low-density regions.

I sped up the sampler by running a bunch of chains in parallel. I read a few papers that warned against this, but I don’t quite understand why. I took the following attitude: If I run a chain for T steps and I think it’s converged to the target distribution, and then I run another chain for T steps with a different starting point, then combining both chains should give a chain of length 2T which has also converged to the target distribution. If that’s true, I should be able to run the chains in parallel. In my experiments, I ran hundreds of parallel chains for thousands of steps to sample around a million points in a few seconds. That gave reliable values for the projected density in MENT.

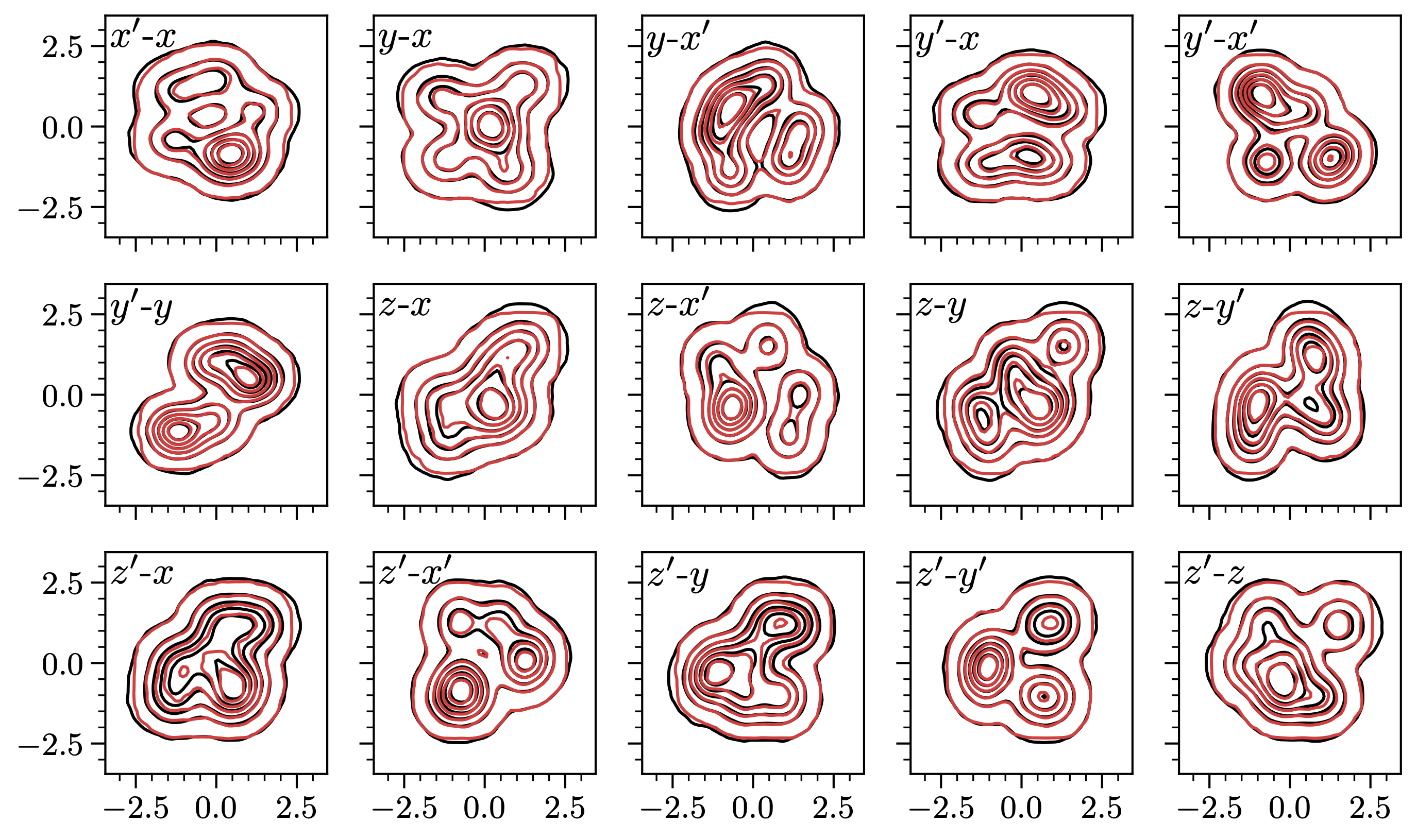

For an initial test, I defined a 6D Gaussian mixture distributions, which is bunch of Gaussian blobs with random positions and sizes. This could be a challenging case for MCMC because the distribution is multimodal. For the training data, I selected the 2D marginal projections: for an N-dimensional distribution, there are N(N – 1)/2 projections. Here’s the result for N=6:

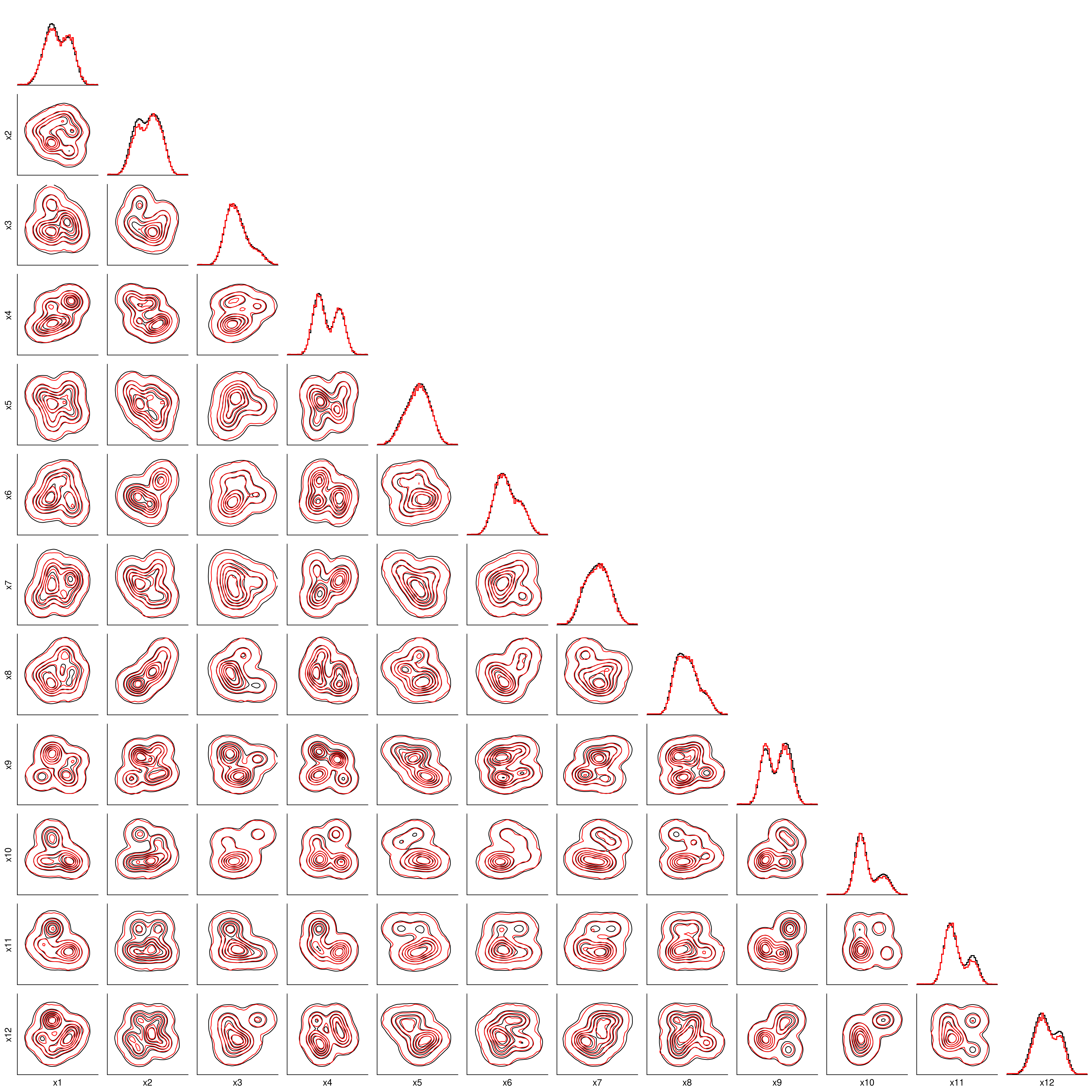

It worked! And just for fun, here’s the same test for N=12:

See the preprint for more details. Also the MENT code is here.