Princeton Muon Collider Workshop

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) will soon double its luminosity, but progress in high-energy physics (HEP) will eventually require a new laboratory [1]. There are a few options. The Future Circular Collider (FCC) would collide ~100 TeV protons in a 100 km ring, using the LHC (7 TeV, 25 km) as a booster ring. The plan would be to start colliding leptons (FCC-ee) in the 2040s and switch to protons (FCC-hh) in the 2070s. The accelerator would be a relatively straightforward extension of the LHC, although there would be some new challenges, especially the required 16 T (!) bending magnets.

An alternative approach is to collide leptons. Hadron collisions distribute energy among quarks and gluons, and it can be difficult to extract signals from the debris. Leptons don’t seem to have any internal structure; their collisions are clean and efficient, enabling precision measurements of certain reactions. Such collisions would be especially useful for studying the Higgs boson. Unfortunately, synchrotron radiation limits lepton energy in circular accelerators. Linear accelerators eliminate this problem but need to by very long to probe BSM physics. The proposed International Linear Collider (ILC) would collide electrons with positrons at ~1 TeV in a ~50 km linac. The ILC has undergone a comprehensive design study and is ready to launch. Japan has shown interest, and although there are no official plans, the ILC could start running as soon as 2035.

A muon collider (MuC) would be a hybrid approach. A MuC would collide muons and antimuons at ~10 TeV in a ~10 km ring (approximately the size of the LHC). Since muons are much heavier than electrons, they can be accelerated to 10 TeV in a compact ring. And since they are leptons, their collisions are more useful than hadrons at the same energy. A MuC is likely the only hope for a collider beyond LHC energy within my lifetime; if all goes well, it could start running in 2045. But there’s a problem: muons decay almost instantly. And another problem: muon beams are hot—they occupy a large volume in position-momentum space. And other problems too, such as neutrino radiation (!). These problems require novel solutions. Thus, the muon collider might be both the fastest and most challenging path to the energy frontier.

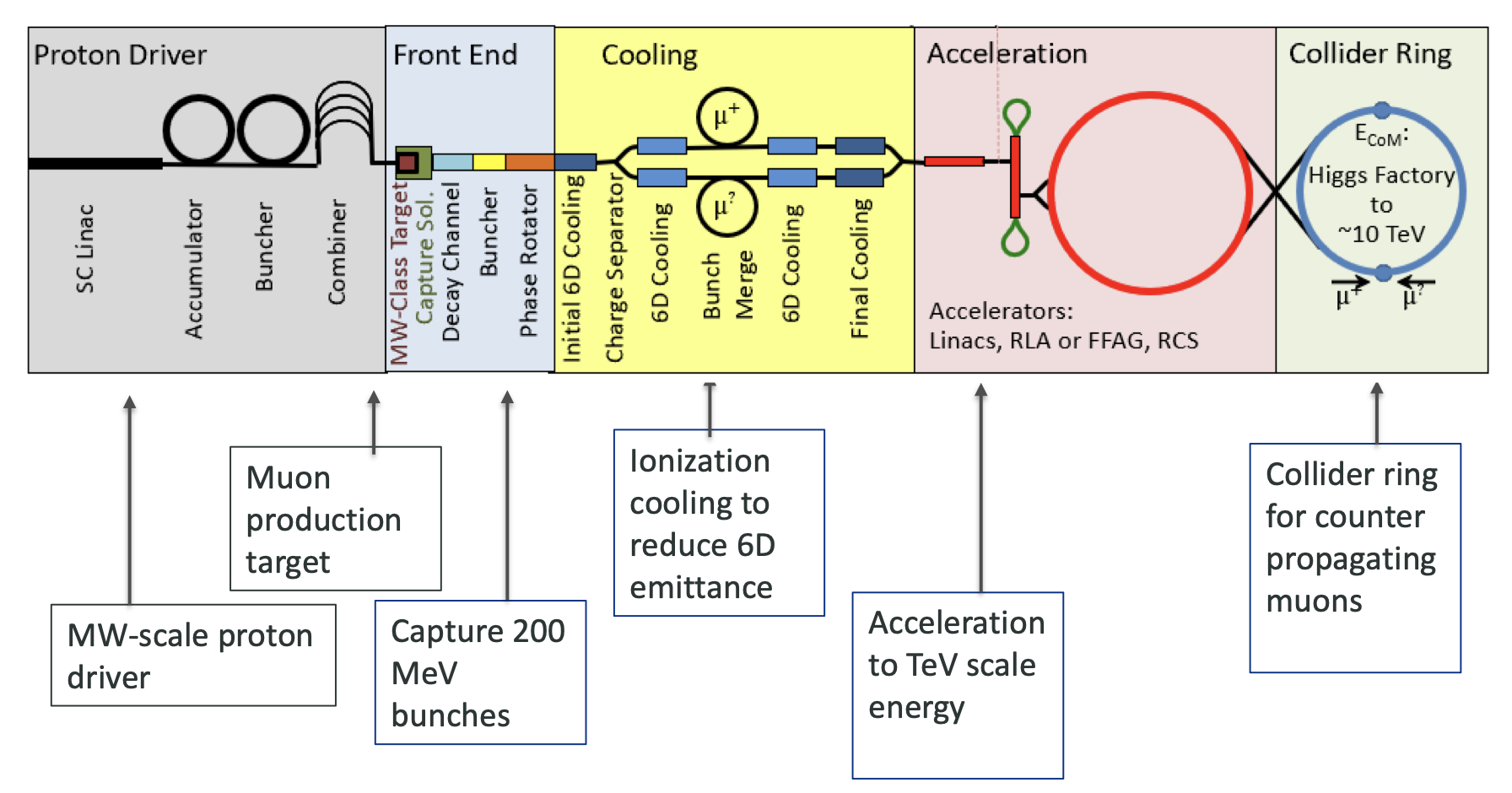

The US Muon Accelerator Program (MAP) developed a preliminary MuC design some years ago, and the International Muon Collider Collaboration (IMCC) has started where MAP left off. The preliminary design is shown below [2]:

The front end generates the muon and antimuon beams by colliding a proton beam with a metal target, the middle section cools the beams, reducing their phase space volume by six orders of magnitude (!), and the final section accelerates and collides the beams at dedicated interaction points. There is a push to deliver a collider design in the next few years, reflecting growing support from the HEP community.

I recently gave a talk at a workshop on muon colliders at Princeton University. The workshop discussed how the US could address the key technological challenges in the next five years. All presentations are available online. I discussed how the SNS could test the extreme proton bunch compression needed to generate the initial muon beam. It was a unique workshop because of the mix of accelerator and particle physicists. While most of the talks focused on accelerator physics, around a third focused on detectors or HEP theory. A major topic was the beam-induced background (BIB) due to muon decay. I didn’t understand these talks well, but they motivated me to resume my particle physics self-education. (I probably would have gone into HEP if I’d attended a different grad school.)

It was interesting to hear the particle physicists’ perspectives. Some expressed a desire for more accelerator-particle physics collaboration, especially among graduate students. I’m not sure how a Ph.D. student could have time to learn both accelerator physics and the complicated data analysis required for experimental particle physics. But I like this idea, and I’m sure many projects would benefit from multiple perspectives and skill sets.

I also liked hearing about the state of HEP. One experimentalist expressed his opinion that particle physicists undersell their work. He drew a comparison to condensed matter physics, where experiments reveal exciting and unpredicted phenomena despite agreeing with the underlying theory of quantum mechanics. He argued that similar findings are commonplace at the LHC — many new processes do not contradict the Standard Model (SM) but are, nonetheless, unexpected and exciting. I suppose material science discoveries will always get more attention because they can lead to new technologies, while particle physics is more out there. In other words, who cares if tetraquarks exist? But from a fundamental scientific viewpoint, these discoveries are equally exciting.

I was happy to attend this workshop and look forward to exploring SNS contributions to MuC design. It’s exciting to think about projects twenty (or even fifty) years away.

A few up-to-date talks on future colliders: IMCC, FCC, ILC.